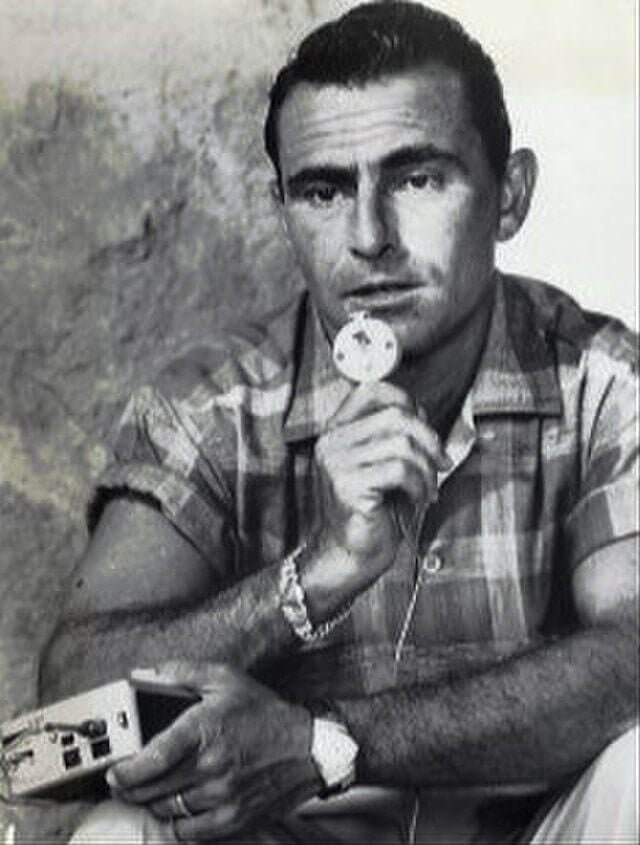

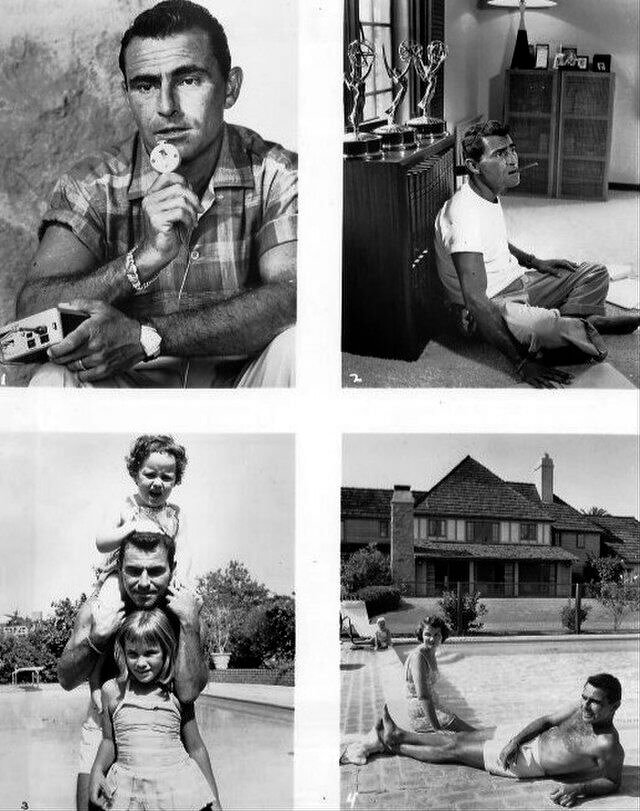

In the 1950’s, television shows in America were predictable and wholesome. That is, until a bold new writer burst onto the scene at the end of the decade presenting stories about the human condition that were both moving and disturbing. Rod Serling was a true artist who created his own television show in the early days of the medium in order to tell stories about people and their triumphs and frailties. The Twilight Zone, the show he created, wrote, produced, and hosted, aired on CBS for five years and has become ever more popular as the years have gone on. Serling’s timeless stories remain examples of some of the best television storytelling ever produced. Here is the remarkable story of Rod Serling, the creator of The Twilight Zone, an extraordinary writer who cared just as much about people and society as he did about the quality of his work.

A Journey Into a Wondrous Land

On Christmas Day, 1924, Rodman Edward Serling was born in Syracuse, New York, to a Jewish family. They moved to Binghamton in 1926 and Serling spend most of his childhood there. From an early age, he was a performer, and his parents encouraged him. His father put together a small theater in the basement of their home, and in it, Rod would perform little plays with neighborhood kids when he could recruit them, or alone when he couldn’t.

By the age of seven, he would amuse himself and his older brother by acting out stories from movies he saw. He could talk for hours, asking rhetorical questions and then immediately answering them himself, or moving on, leaving them unanswered. Once, on a two-hour road trip, Rod told stories the entire way from Binghamton to Syracuse while the rest of his family didn’t say a word. He never noticed their silence.

The Class Clown Joins the Debate Team

In grade school, no one knew what to do with him. Rod was the class clown, always talking, interrupting, and making jokes. Most of his teachers thought that there was little hope for him and wrote him off as a lost cause. But in seventh grade, his English teacher, Helen Foley, saw his potential and encouraged Serling to join the debate team, where his love for talking could be put to good use.

He excelled at debate and public speaking generally, and ended up speaking at his high school graduation. He also began writing for his school newspaper, where he quickly earned the reputation of being a social activist. His passion for social justice remained with him for his entire life, and was actually a key factor in his creation of The Twilight Zone, as we shall see. He was also interested in sports, and played tennis in high school.

He Supported America’s Role in World War Two

While in high school, World War Two was raging, and Serling was a big advocate for American involvement. He saw what was happening in Europe and felt that the US had a moral obligation to intervene. He became the editor of his high school newspaper, and in its pages, he editorialized about the necessity of the US war effort. He encouraged his fellow classmates to join and fight.

In fact, Serling almost quit high school to join the military himself, but a teacher named Gus Youngstrom persuaded him to graduate first, reminding him that war was temporary, but education was forever. "War is a temporary thing," Youngstrom reminded Serling. "It ends. Education doesn't. Without your degree, where will you be after the war?" Serling decided to finish high school, and graduated in 1943. The very next day, he went to the recruitment office and signed up to join the Army.

Horror in the Philippines

Serling had hoped to be sent to Europe to fight the Nazis, but to his disappointment, he was sent to California and the Pacific to fight the Japanese. He was trained as a paratrooper and stationed in the Philippines. Although he wasn’t the most enthusiastic fighter, he was a keen observer of people. He sometimes wandered off and got lost, and one time failed to reload his rifle when his company was under attack.

But he also showed moments of selfless bravery. Once, a party being thrown by locals to thank the Americans for driving the Japanese away came under attack. Serling ran on stage to rescue someone who was performing, despite the heavy gunfire. In the end, half of his regiment died while on duty, and Serling himself was hit with shrapnel and received a Purple Heart, as well as a Bronze Star and the Philippine Liberation Medal.

World War Two Themes Appear in His Later Work

Serling’s experiences during the war greatly influenced both his political and his artistic perspective. A few Twilight Zone episodes are set in the Philippines during wartime, and depict the horror to which Serling was exposed on a daily basis. More than a few episodes deal with the unpredictability of death and depict people in situations over which they have no control. Serling later said, "I was bitter about everything and at loose ends when I got out of the service. I think I turned to writing to get it off my chest."

After the war, Serling attended Antioch College in Ohio. He spent most of his time at college in the theater department and the broadcasting school. He was also very active with his college radio station. It was there that he began writing, directing, and acting in radio dramas. He graduated with a degree in Literature in 1950.

His Side Hustle Was Testing Parachutes

For his first few years in college, Serling earned extra money by testing parachutes for the US Army Air Forces. He had been trained as a paratrooper, so he was comfortable jumping out of planes, and he felt like it was easy money, despite the obvious risks. According to colleagues at the college radio station, Serling got $50 for each jump, with special pay for extra dangerous ones.

If the jump was really experimental, he would get $500 for a jump, with half paid in advance, and the other half paid after he survived. And once he was paid $1000 for testing a jet aircraft ejection seat system that had killed the last three people that tried it. His last jump was only about a week before his wedding to Carol Kramer, a fellow Antioch student. They married in July of 1948 and had two daughters together, Anne and Jodi.

His Early Writing Days

Serling began writing for his college radio station, and produced mostly dramatical radio plays. While other writers create novels or short stories, and some write plays, Serling was drawn to the kind of dramatical pieces that could be produced for radio, and later, television, in a relatively short period of time. Talking about those early days, he would later say, "I learned 'time', writing for a medium that is measured in seconds".

In addition to writing for his own station, he would sometimes try to write for other shows. A popular show at that time, Dr. Christian, a show about a doctor who delivers quintuplets, held a contest for which anyone could submit a screenplay. Serling’s submission, "To Live a Dream" was selected among thousands of scripts sent in. He was paid $500 for it. He also wrote as a freelancer and staff writer before starting to write for television.

“Patterns” Puts Him on the Map

The first script that Serling wrote which got him a lot of positive attention was an episode of Kraft Television Theatre entitled “Patterns”. “Patterns” was first broadcast as an hour-long, live television play on January 12, 1955, and got rave reviews. The script was about office workers in the business world, and was heralded for being one of the best things to appear on the nascent medium of television.

Jack Gould of The New York Times said about it, “For sheer power of narrative, forcefulness of characterization and brilliant climax, Mr. Serling's work is a creative triumph that can stand on its own.” Television critic Tom Shales wrote enthusiastically, “Serling pulls a viewer almost immediately into his story, a tale of corporate morality—or the lack of it—and such everyday battles as the ones waged between conscience and ambition. The show was performed again a month later, live on national television.

Requiem for a Heavyweight

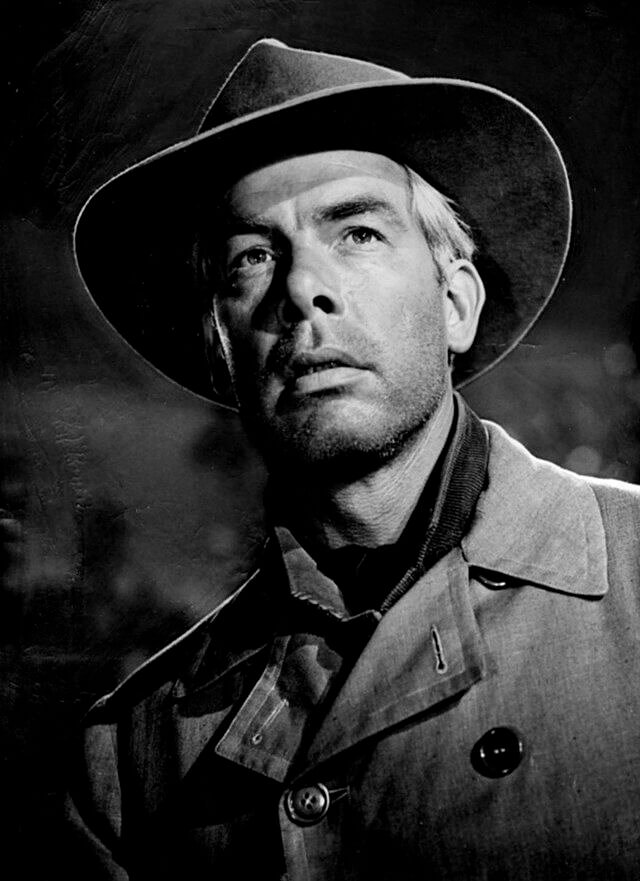

Serling won his first of six Emmys for writing “Patterns”, and as a result of its two broadcasts, Serling became a writer very much in demand in television. In 1956, Serling wrote a script for Playhouse 90, CBS’s television anthology drama series that featured 90 minutes live performances of dramas, compared to the hour-long length of most other shows of that type. “Requiem for a Heavyweight”, the script that Serling ended up writing, was a masterpiece.

It’s still considered one of the best works of live television drama in history. The show is about a boxer at the end of his career, and the manager he trusts but who is ultimately using him. The show won Serling another Emmy, and was later expanded into a feature-length motion picture. The following year, television networks began taping shows instead of broadcasting them live, and Serling moved to California to begin working there.

Serling’s Perspective on Social Activism

Serling moved to California to write for television shows. He was coming off the incredible success of “Patterns” and “Requiem for a Heavyweight”, and he was very much in demand. But he thought of writing as more than entertainment. Going back to his high school days, he thought that writers had a responsibility to speak up about social issues and causes.

Whether it was the importance of fighting fascism in WW2, or civil rights and other important issues of the day, he felt that writers had to take a stand. “The writer’s role is to be a menacer of the public’s conscience,” he explained in interviews. “He must have a position, a point of view. He must see the arts as a vehicle of social criticism and he must focus on the issues of his time.” The real turning point for him happened after the horrible murder of Emmett Till.

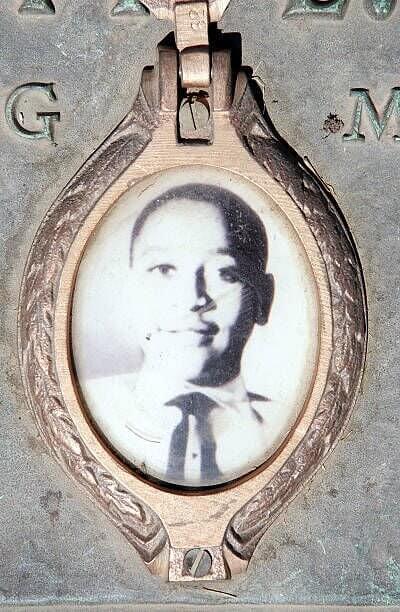

The Tragic Tale of Emmett Till

Emmett Till was a young African American who was killed in the deep South in 1955 and subsequently became an icon for the burgeoning civil rights movement. Till was a 14-year-old boy from Chicago who was visiting relatives in Mississippi. While in a local grocery store buying candy, he had an encounter with the 21-year-old co-owner of the shop, a white woman named Carolyn Bryant. It’s unclear what happened inside the store, but locals were outraged that a young black man would even talk to a white woman.

Two men kidnapped him, tortured him, and murdered him. His body was horribly disfigured, and caused national outrage among the Black community, which increased dramatically after the two murderers were found not guilty by an all white jury. The case highlighted the incredible injustices being perpetrated on African Americans, and directly led to the next phase of the civil rights movement.

Serling’s Reaction to Racial Injustice

Rod Serling felt strongly about issues of social justice, and like many American Jews of the time, was a strong advocate for civil rights for African Americans. Serling was outraged at the miscarriage of justice in the Emmett Till case, and immediately set out to write a script about the evils of prejudice and discrimination. However, networks at the time were very wary of producing anything controversial, for fear that it would drive away viewers.

Sponsors, too, were cowardly when it came to divisive issues because they didn’t want to drive any customers away from buying their products. The show Serling wrote for the program U.S. Steel Hour on ABC was called “Noon on Doomsday”, and was about a Jewish pawnbroker who was lynched in the deep South. However, even though Serling removed any overtly racial aspects to his script, after an interview Serling gave, all hell broke loose.

Forced to Change His Script

Serling knew that civil rights was a touchy issue, and wrote his script about a Jewish victim of a lynching in the South instead of a Black one. But even that was too close for some people. In an interview with the Daily Variety, Serling mentioned that his latest script was about the Emmett Till case, and the story was picked up by newspapers all over the country.

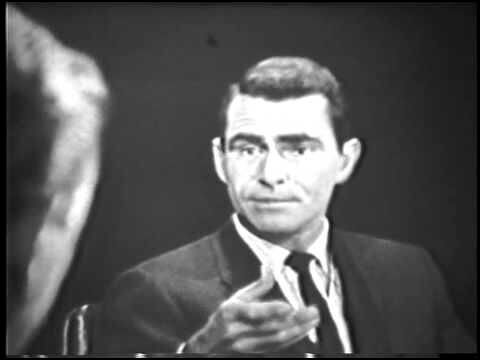

Thousands of letters began pouring into both ABC and U.S. Steel condemning the upcoming show. Even though most were from overtly white supremacist groups, the corporations quickly surrendered and changed the script to appease the racists. In an interview with Mike Wallace, Serling described it as a systematic dismantling of his story. They took out all references to the Till story, including “taking Coca-Cola bottles off the set because the sponsor claimed that this had Southern connotations”, as he told Wallace.

His Subsequent Script Suffered the Same Censorship

Serling was disappointed in how his script about Emmett Till had been eviscerated, and decided to try again. He penned a new script for CBS’s Playhouse 90 called “A Town Has Turned to Dust”, also about a lynching, but this time set in the southwestern US. CBS executives forced him to set the story 100 years in the past. Still, the story came a lot close to expressing how Serling felt about racial discrimination.

The end of the show featured a soliloquy delivered by a journalist writing home to his editor, and such speeches at the end of the episode soon became a trademark of Serling’s scripts, especially on the Twilight Zone. The soliloquy contained the following conclusion: “Two men died within five minutes and fifty feet of each other only because human beings have that perverse and strange way of not knowing how to live side by side.”

Corporate Censorship Gets Annoying

It was difficult enough with the networks and sponsors whitewashing Serling’s scripts about Emmett Till to remove any mention of race or the South. He was willing, however, to make some changes in order to say what he wanted to say. As he expressed later in an interview, “If you want to do a piece about prejudice against [African Americans], you go instead with Mexicans and set it in 1890 instead of 1959.”

Even worse were the seemingly capricious and arbitrary incidents of censorship that his scripts faced from the corporate sponsors. Anything that the corporations feared would remind the viewer of a competitor was summarily redacted from his scripts. In “Requiem for a Heavyweight”, the line "Got a match?" was taken out because one of the sponsors of the show was Ronson lighters. Censorship had really become a problem for Serling, and he looked for ways to avoid it.

There Was Only One Solution: His Own Show

Corporate and network censors were having a real effect on Serling’s scripts. In one instance, a line that mentioned the Chrysler Building was removed from a script because Ford Motor Company was one of the sponsors. In another, a scene in which a litter of puppies was born in a barn was removed because the sponsors, a conservative corporation, were afraid that a scene where an animal gave birth would remind viewers of sex.

Serling realized that the only way to avoid that kind of censorship was to write and produce his own show. That way, he could pick his sponsors and ensure they wouldn’t interfere creatively. In the Mike Wallace interview, he said, “I don't want to fight anymore. I don't want to have to battle sponsors and agencies. I don't want to have to push for something that I want and have to settle for second best.”

He Made His Peace With Corporate Sponsorship

One of the factors that drove Serling to create The Twilight Zone was interference and censorship from sponsors. The last straw was when an appliance company objected to a script about the Holocaust that was being produced by Playhouse 90. He told Mike Wallace about the episode, describing it as “a lovely show called ‘Judgment at Nuremberg’; I think probably one of the most competently done and artistically done pieces that 90’s done all year”.

The show mentioned the gas chambers, and for the broadcast, that line was completely cut, even though the gas used in the Holocaust had nothing to do with the gas that’s used in kitchen appliances for cooking. The sponsor, Serling told Wallace, “did not want that awful association made between what was the horror and the misery of Nazi Germany with the nice chrome wonderfully antiseptically clean beautiful kitchen appliances that they were selling.”

Desilu Stole His Twilight Zone Pilot

Serling approached CBS with a script that he intended to be the pilot of a new show over which he could have full creative control. The script was called “The Time Element” and it was about a psychiatrist whose patient is having recurring nightmares about the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that precipitated America’s involvement in WW2. As the story unfolds, we learn that it is the psychiatrist who is actually having the realistic nightmares, and the patient in his dreams actually died at Pearl Harbor.

It was the kind of twist ending that Serling later became famous for and which appeared in many episodes of The Twilight Zone. CBS loved the script and bought it, but then decided to use it with a different show, The Westinghouse Desilu Playhouse, with its executive producers Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. The show was broadcast in 1958 and was very positively received.

The Twilight Zone Was Greenlit

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz were a powerful Hollywood couple at that time, and they certainly were able to convince CBS to let them use Serling’s script for their show. Once the show was aired, however, CBS saw the potential in Serling’s work and decided to support his show. He insisted on having creative control. He made sure he only hired scriptwriters that he liked and respected, including Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson, and he only worked with sponsors who wouldn’t change his scripts.

Possibly the most important thing he did to ensure the artistic integrity of his new show was to make it a science fiction/fantasy program. That way, no one would think the stories related to any actual events, and he could write about the human condition without interference. His Twilight Zone scripts make strong statements about prejudice and human rights, and about the strength of women.

“A Good Working Relationship”

With The Twilight Zone, after long meetings and difficult negotiations, Serling was able to convince sponsors to give him full creative control. Serling told Mike Wallace in his 1959 interview, “in questions of taste and questions of the art form itself and questions of drama, I’m the judge, because this is my medium and I understand it. I’m a dramatist for television. This is the area I know. I’ve been trained for it.”

“I’ve worked for [television] for twelve years, and the sponsor knows his product but he doesn’t know mine. So when it comes to the commercials, I leave that up to him. When it comes to the story content, he leaves it up to me.” Over the first 18 shows, only one thing was changed by a coffee company sponsor. It was a line in which a sailor on a ship asks for a cup of tea.

Twilight Zone Production Notes

With the success of his script “The Time Element” that was produced for Desilu, Serling was in a position to create The Twilight Zone the way he wanted. CBS agreed to produce it together with Serling’s production company, Cayuga Productions. This meant that Serling owned half the show. He was also the executive producer and lead scriptwriter. He was paid $10,000 per script just for the writing, which was a tidy sum in those days.

In the end, Serling penned 96 out of the 157 episodes of the Zone. Some he wrote in as little as a day if the schedule demanded it. Because each show was independent, to instill a bit of continuity, CBS suggested that they have a narrator. The famous actor and director Orson Welles, with his deep baritone voice, was their first choice, but he was too expensive. Serling decided to narrate the show himself.

Origin of the Name

The name The Twilight Zone is now a permanent part of the American vocabulary. Nearly everyone has seen the show or at least has heard of it. It evokes a strange feeling of liminality, a place in between worlds, a hidden reality just beneath the surface of ordinary, mundane life as we know it. The term originally comes from a common staying in the US Military. The military is famous for coming up with memorable phrases.

Two famous examples of military acronyms that have crossed over to be used extensively in civilian life are FUBAR, which stands for F-ed Up Beyond All Recognition, and SNAFU, which means Situation Normal, All F-ed Up. The Twilight Zone was a term used by military aviators to describe the moments when a plane can’t see the horizon. The implication was that the show portrayed the human condition by obscuring the usual view of things.

The First of 156 Episodes About the Human Condition

On October 2, 1959, The Twilight Zone premiered with the episode, "Where is Everybody". In an era of Ozzie and Harriet and Father Knows Best, putting ordinary characters in bizarre and unusual situations, many of which remained unresolved at the episode’s end, was unheard of. In the episode, an Air Force pilot arrives in a small, Western town to find it devoid of people. He wanders around the abandoned ghost town and starts to feel desolate and desperately lonely.

He soon goes stark raving mad thinking someone is watching him. In the end, it’s revealed that he is being tested by the government. He’s actually been in an isolation booth for over 20 days to see if he can handle the solitariness required for space travel. He could not. The viewer is left with the discomfiting, uneasy feeling that they would often have while watching future episodes of the series.

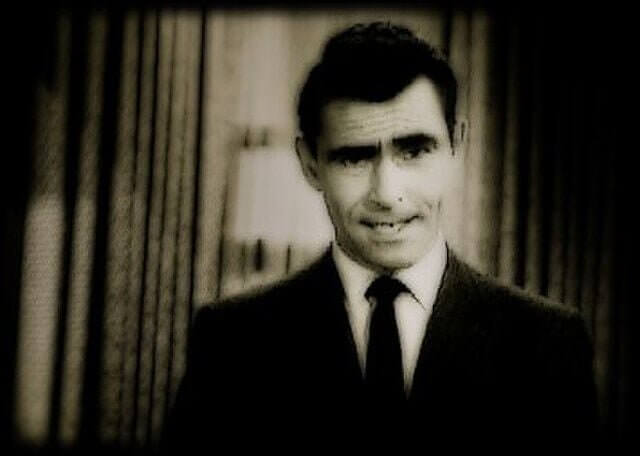

The Famous Introduction

The Twilight Zone began with a mysterious introduction that was an instant classic. The first episode opened with the words, “There is a fifth dimension beyond that which is known to man...it is the middle ground between light and shadow, between science and superstition..this is the dimension of imagination”, and immediately set the tone for the series. Over the years, there were several different versions of the iconic opening.

A famous variation went, “You're traveling through another dimension -- a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination. That's a signpost up ahead: your next stop: The Twilight Zone!” The last four episodes began, “You are about to enter another dimension. A dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land of imagination. Next stop—The Twilight Zone.”

“To Serve Man”

This classic episode was first broadcast on March 2, 1962 in the third season. The teleplay was written by Rod Serling from a short story by Damon Knight. Aliens land on Earth during a time of great international conflict and announce that they have come on a humanitarian mission; they wish to share their technology and help end war and famine, and provide unlimited electrical power. They leave a mysterious book behind and leave.

People are initially skeptical, but finally, a cryptographer named Patty is able to translate the title of the book: “To Serve Man”. Convinced of their sincerity, volunteers begin traveling to the planet by the thousands. Patty finally translates the rest of the book, and to his horror, he discovers that it’s actually a cookbook, and all the volunteers have been eaten by the aliens. The ending ranks as one of the best twists of all time.

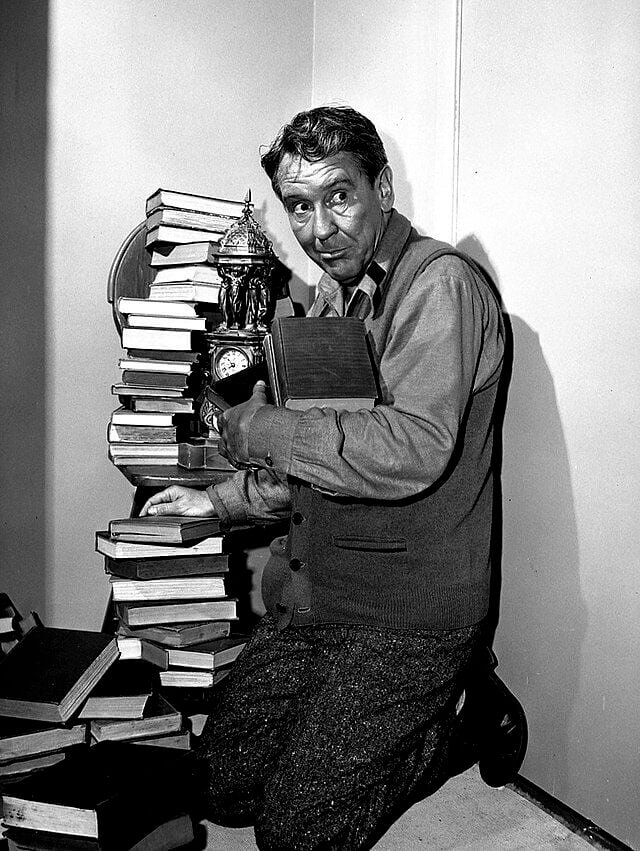

“Time Enough at Last”

One of the most famous and beloved episodes, this one stars Burgess Meredith as a humble bank employee who wears thick eyeglasses and loves to read more than anything. Every day, he would eat his lunch in the bank’s vault because that was the only place he wouldn’t be interrupted; all he wanted was more time for reading. One day, a huge explosion rattles the vault.

He realizes that a nuclear war has killed everyone and destroyed his city, but the vault protected him. He stumbles to the library and happily discovers that all the books are intact; he finally has the time and solitude to be able to read as much as he wants. Suddenly, he stumbles and breaks his eyeglasses. Without them, he can’t read, and so ultimately he is alone and heartbroken, with books nearby but no way to read them. He needed society after all.

“The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street”

This remarkable episode touched on the themes of prejudice and how fear and paranoia can turn neighbors against each other. On a street that could be anywhere in America, a meteor passes overhead and all electrical devices turn off. Rumors begin to spread that aliens have landed, and that some of their neighbors are aliens who have been sent early as scouts. Gradually, all the townsfolk begin to suspect one another.

Before the night is over, they are shooting each other dead, each convinced everyone else is an alien. Meanwhile, high above, the real aliens are watching the Earthlings destroy each other without having to do a thing. As Serling reminds us in the closing monologue, “The tools of conquest do not necessarily come with bombs and explosions and fallout. There are weapons that are simply thoughts, attitudes, prejudices... to be found only in the minds of men.”

He Took on the Issues of His Day

Throughout its run, The Twilight Zone tackled themes that were very much on the minds of Americans at that time. The Cold War was in full swing, with the threat of nuclear annihilation always looming, and episodes like “Time Enough at Last” and “Third From the Sun” concerned the end of the world. Issues of racial prejudice were still important to Serling, and that led to episodes like “The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street” and “I Am the Night—Color Me Black”.

With the world of science and technology progressing so rapidly even then, episodes like “Walking Distance” and “A Stop at Willoughby” that expressed the yearning gravity of nostalgia were also presented. In total, 156 episodes were produced over five seasons, after which Serling was so exhausted that he didn’t object to the network canceling the show. He had had a great run, and wanted to try other things.

A Land of Both Shadow and Substance

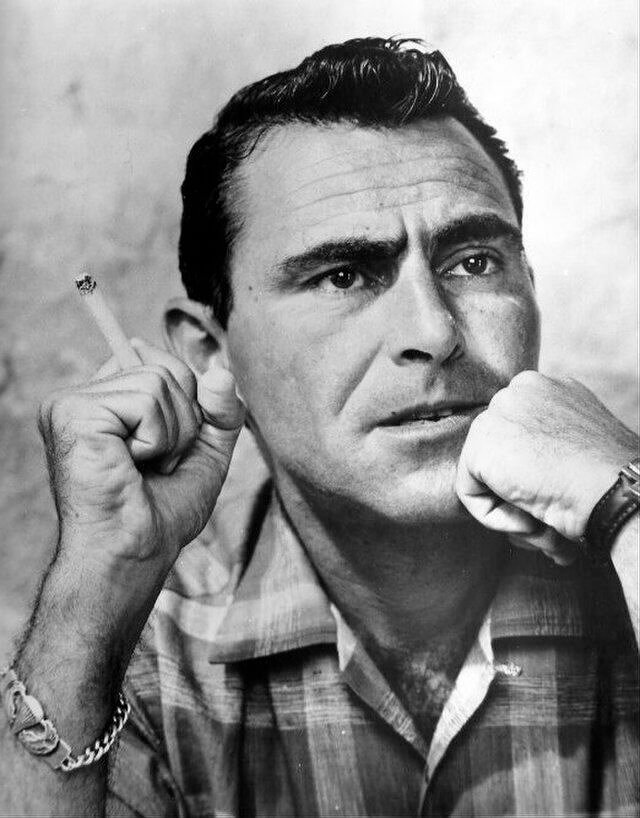

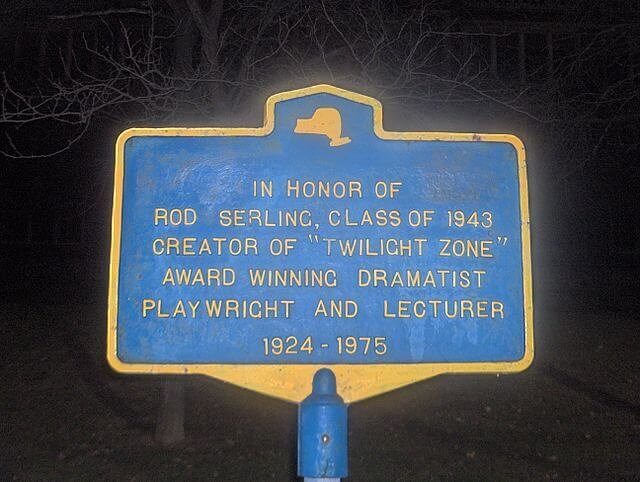

After the success of The Twilight Zone and due to his very visible role as its host and creator, Rod Serling became one of the most celebrated and successful writers in television. He continued to write and teach at Ithaca College near his hometown in New York until his five-pack-a-day cigarette habit finally caught up with him at the age of 50 and he died in 1975. He never stopped speaking out to oppose war and to encourage the noblest aspects of humanity.

Serling’s legacy lives on to this day. He introduced viewers to a new kind of television, one which entertains yet also provokes- one which doesn’t hide from the important issues of the day but instead faces them head-on, without preaching any particular perspective. It was perhaps the first show to truly respect its audience, and perhaps that’s why Rod Serling is still so admired today.