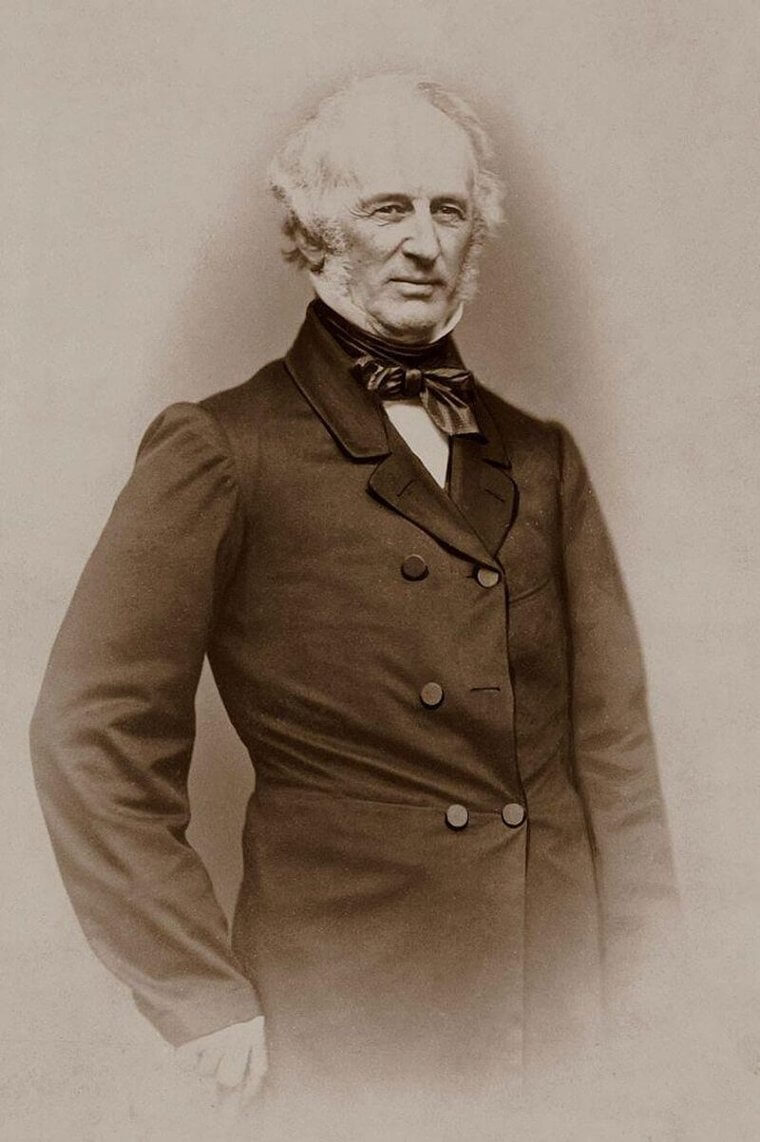

Cornelius Vanderbilt was born into poverty. He left school at the age of 11 to start work and help his family financially. But he was destined for more, and he never let anything or anyone stand in his way. By the age of 16 he had set his business empire in motion. His story reveals just how far hard work can take you - as long as you’re not afraid of making enemies.

This family is one of the most fascinating, and at times complicated, in American history. If you’ve ever wondered how Commodore went from a poor farmer’s son to a millionaire business owner, these captivating facts about him and his family tree will enlighten and perplex you. From his rocky first marriage, his 11 surviving children, and the enemies he made along the way, here’s everything you should know about the Vanderbilts.

This family is one of the most fascinating, and at times complicated, in American history. If you’ve ever wondered how Commodore went from a poor farmer’s son to a millionaire business owner, these captivating facts about him and his family tree will enlighten and perplex you. From his rocky first marriage, his 11 surviving children, and the enemies he made along the way, here’s everything you should know about the Vanderbilts.

1794: Commodore Was Born Into a Humble Family

Coming from the Netherlands, the Vanderbilts settled into the United States in the late 17th century. They lived mostly simple lives, with much of the family being farmers and Cornelius’ father making his living by ferrying produce from Staten Island to Manhattan on his boat.

The birth of Cornelius in 1974 marked the start of the family’s name skyrocketing into money and fame - although they didn’t know it then. It was Commodore’s (as Cornelius became known) humble beginnings that helped him get to where he ended up.

1810: The Commodore’s Wealth Began With a $100 Loan

When Cornelius was 16, he took a loan of $100 from his parents. This would be worth around $2000 today. He used the money to buy a periauger (a flat-bottomed sailing barge) which was the same type of boat that his father was using for his produce ferrying business.

In return for loaning him the capital, Cornelius agreed to share his profits with his parents. In his first year of transporting cargo, the Commodore became a ruthless businessman and made 10 times the amount that he loaned. He also increased his fleet size.

1812 - 1827: Cornelius Continued to Make Smart Business Decisions

At 18, Cornelius secured a contract with the US government during the War of 1812, which had him supplying outposts. While he was transporting goods and people to Delaware Bay from Boston, he continued to learn more about the business of open water sailing. He had earned $10,000 in revenue by the end of the war.

With his growing fleet and knowledge, Cornelius went into business with Thomas Gibbons, who owned Union Line. This partnership led to a court case filed by Robert Fulton, Robert Livingston, and Aaron Ogden since they were violating the state monopoly over shipping by the latter. But Union Line was allowed to continue and ended up making over $40,000 a year by 1827.

1813: Vanderbilt Married His Cousin Sophia Johnson

While he was building his business, Vanderbilt got married to his cousin, Sophia Johnson. Cornelius was 19 and had a booming business going, Sophia was 16, and the family was not pleased about the union. Together, the pair had 13 children, but unfortunately, two did not make it to adulthood.

While Vanderbilt was a great businessman, he was not a very good husband. He’s believed to have cheated on his wife with prostitutes and apparently tried to have her committed to an asylum after he showed romantic interest in the family's young governess. Sophia died in 1868, and a year later Cornelius got remarried. His second wife was Frank Armstrong Crawford Vanderbilt, an American socialite, and philanthropist.

1814 - 1839: The Vanderbilt Children Battled to Gain Their Father’s Approval

Just as Commodore didn’t do much justice to his role as husband, he battled in the role of father as well. Of his 13 children, he had three sons but would have preferred more. That caused a divide in his relationship with his daughters.

One of his sons, George, sadly didn’t make it to adulthood. The other two, William Henry and Cornelius Jeremiah had a hard time living up to their father’s expectations. William especially received harsh judgment from his father, often called a "blatherskite," and suffered a mental breakdown very young. Although he eventually went on to inherit most of his father’s fortune.

1817: Cornelius Built His Empire From The Ground Up

Thanks to his impoverished parents, Vanderbilt had to work especially hard to earn his place in the business world. After making a name for himself in the steamship industry, his ruthlessness and cunning business skills earned him as many enemies as it did dollars. At one point his competitors were paying him to stop operating.

But even when Cornelius had made his successes operating and building ships, and had entered the railroad business, he still wasn’t fully accepted. The Vanderbilt’s first impressive home was built at 10 Washington Place, but the neighborhood elites took a while to welcome the family into their circles.

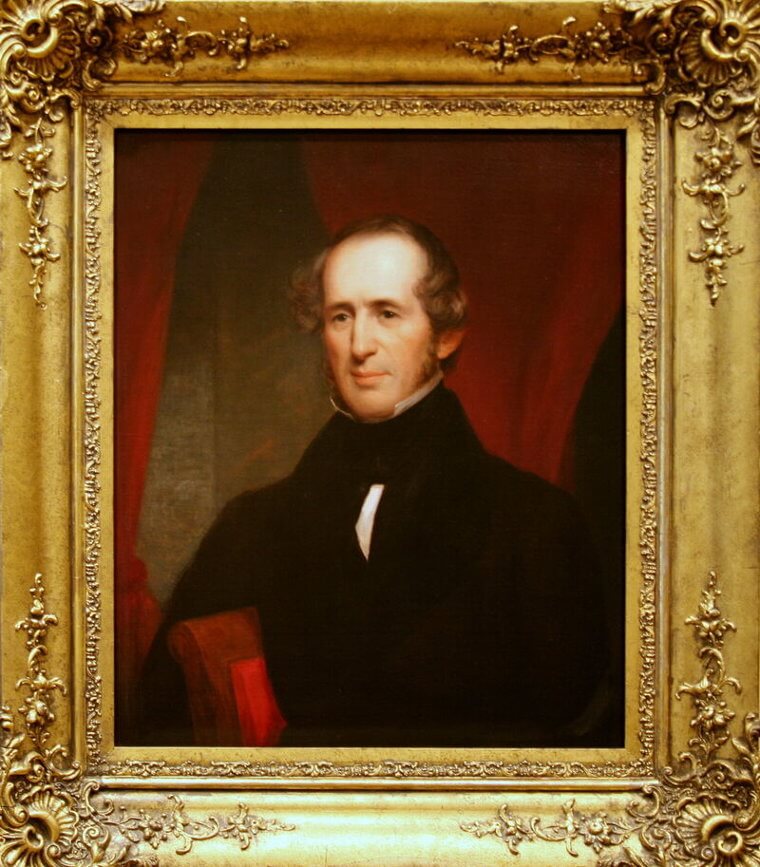

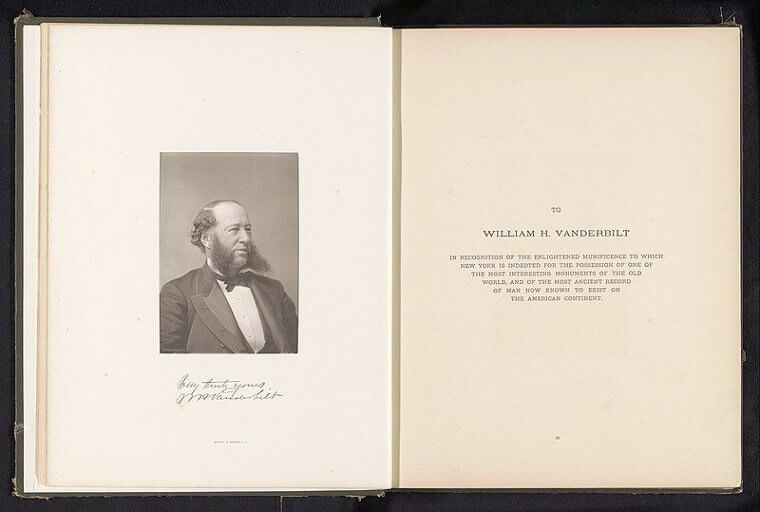

1821: William Henry Vanderbilt Is Born for a Life of Hard Work

In 1821, William Henry (aka Billy) was the first-born son of Cornelius and Sophia. As the eldest, he was held to quite high standards in his father’s eyes. He was constantly berated and had a hard time proving his worth. But he worked hard and trained in business, making him just as skilled as his dad.

Even after Commodore was so hard on him, he still ended up working the closest with the family business. And he received the biggest part of Vanderbilt’s company after he died. William had eight of his own children, including four sons. When Billy died his fortune was divided among them, with the family company stakes going to his two eldest sons.

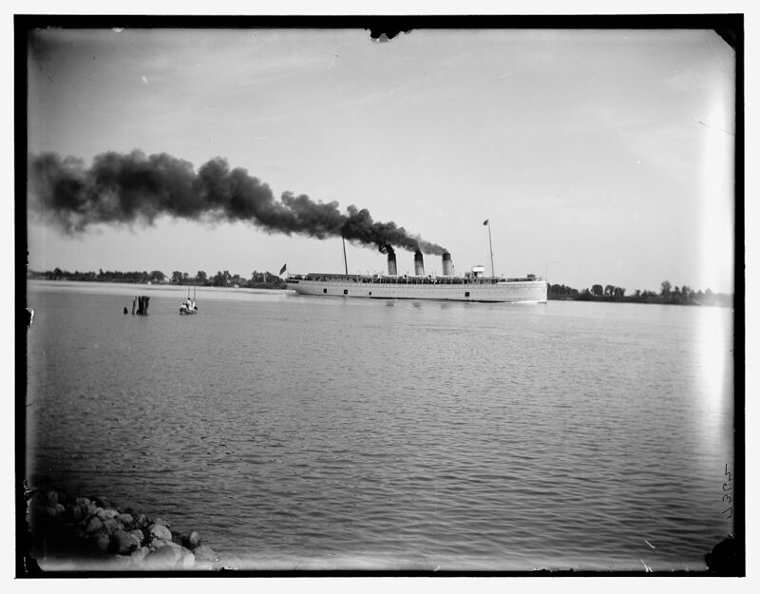

1830 - 1850: Vanderbilt Took Over the Seas and Then the Railways

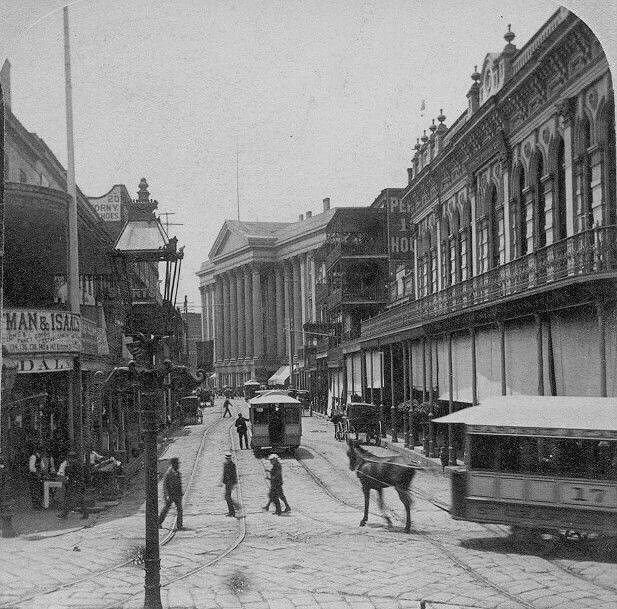

Commodore tried to buy out Thomas Gibbon’s son’s half of the business but was unsuccessful. Not happy with sharing his success, Vanderbilt started the Dispatch Line on his own. This forced Union Line to sell since Dispatch Line was taking over. Vanderbilt continued this trend, buying out his competitors until he all but owned the sea routes along the East Coast.

Then Commodore set his sights on the railways, creating a monopoly by eventually controlling much of railroads in and out of New York City. This ruthless and calculated business mind played a big part in Vanderbilt becoming a millionaire by the time he was 50. A massive shift from his poorer childhood.

Early 1850s: The Gold Rush Brought a New Steamship Service for Vanderbilt

Commodore set up a steamship service during the California Gold Rush in the early 1850s - way before transcontinental railroads. This serviced routes from New York to San Francisco via Nicaragua and was used to transport prospectors to and from.

This route was much faster than any of the others that were available at the time. This made the new service an instant success and helped Commodore bring in over $1 million in just one year.This route was much faster than any of the others that were available at the time. This made the new service an instant success and helped Commodore bring in over $1 million in just one year.

1868: Commodore Fought Tough in the Erie Railroad War

The Erie Railroad War of 1868 saw Vanderbilt going against Jim Fisk and Jay Gould in an infamous battle for financial control of the Erie Railroad. The battle included Vanderbilt buying watered-down shares, spurred on by Daniel Drew who controlled Erie

Ultimately, Drew was pushed to retire, and Fisk and Gould gained full control of the railroad. Even after failing to gain control of the Erie railroad, Commodore continued, unbothered, and became the driving force behind Manhattan’s Grand Central Depot construction in 1871.

1875: Respected Socialite, Alva Belmont Becomes a Vanderbilt

While the Vanderbilts were making plenty of money, they were still having a hard time gaining respect from the elite families of New York. But that changed when Commodore’s grandson, George married Alva Belmont, an intelligent and inspired multi-millionaire American socialite.

If she had been born during any other time, she would have become an architect. But she didn’t let her brain go to waste. Alva was involved in politics and worked on movements that helped women’s suffrage. She was also an important player in introducing the Vanderbilt family into a more respected society.

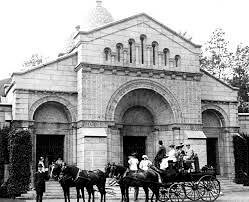

1877: Vanderbilt Dies, With a Net Worth of More Than $100 Million

In January 1877, Commodore died at the age of 82, in his Manhattan home. By the time of his death, Vanderbilt was worth an estimated $100 million. And because Commodore didn’t spend his money on frivolous things or make sizable donations, much of this was still money.

Vanderbilt was buried at the Moravian Cemetery in New Dorp, Staten Island. The majority of his fortune was left to his oldest son, William. After Commodore’s death, his descendants began to spend money in the same way other elites did, building mansions, having parties, and buying expensive items.

1880s: Vanderbilt’s Move to New York and Become Socialites

In the 1880s, with Alva’s help, the family began integrating into New York’s upper social circles. They also bought and built several properties on Fifth Avenue in New York City. This included the impressive Cornelius Vanderbilt II House, which had 130 rooms, a large salon, a two-story ballroom, a gallery, and separate dressing rooms.

Eventually, Fifth Avenue became known as ‘Vanderbilt Row’ since so many of the homes on the roads belonged to the family. This undoubtedly helped the rest of New York’s rich and famous welcome the family.

1880s: The Younger Vanderbilts Led Extravagant Lives

In order to keep up appearances, Commodore’s children and grandchildren took a different financial approach to their millionaire father/grandfather. They spent their money almost as fast as they made it. All by building extravagant homes and furnishing them with expensive decor and artworks.

They also hosted the Vanderbilt Ball, organized by Alva in 1883, which was supposed to help them climb higher in social status. There were 1000 invites to the ball, and it was estimated to cost around $250,000 at the time.

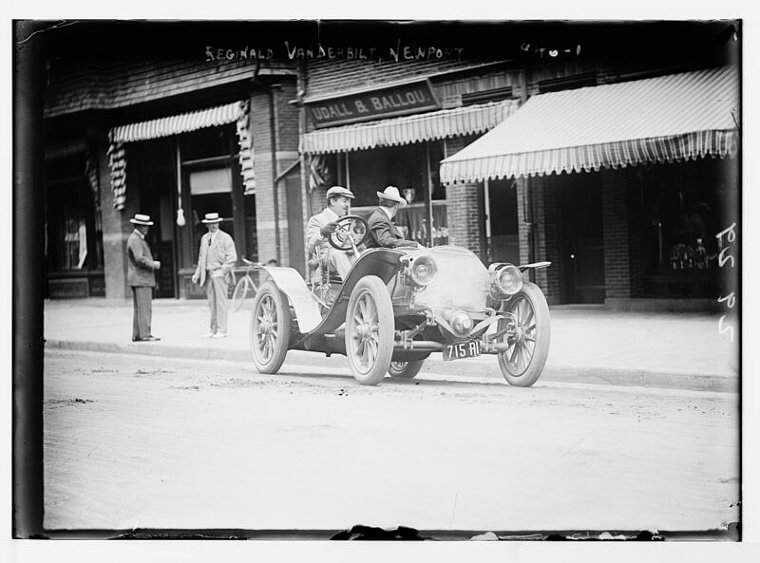

1880 - 1925: Reginald Vanderbilt Lived a Tumultuous Life

Reginald Vanderbilt was Cornelius Vanderbilt II's youngest son, born in 1880. He received a tiny bit of his father’s fortune but lost much of it to his older brother Alfred. He is also the father of Gloria Vanderbilt, the daughter he had with his wife, 17-year-old Gloria Morgan.

Reginald didn’t marry until he was past his 40th birthday. This is mostly due to the fact that he was a known playboy, gambler, and heavy drinker. He spent $70,000 of his $15,5 million inheritance on a gambling table for his 21st birthday. He died two years after marrying Gloria, succumbing to cirrhosis of the liver, and didn’t make or leave much money for his young family.

1885: William Henry’s Fortune Was Divided Between His Eight Children

When William Henry, Commodore’s oldest son, died in 1885, his fortune was split among his four sons. Cornelius II was the eldest and got $80 million, which he used smartly. Cornelius II acquired The Breakers in Newport, Rhode Island, and eventually turned it into a villa.

Of Billy’s other sons, William Kissam received $60 million, and the two younger boys - Frederick and George Washinton II - got $10 million each. Frederick also used his money wisely, investing in coal, tobacco, oil, and steel. This made him much more money than his older brother made.

1987: Vermont’s Shelburne Farms

Eliza ‘Lila’ Vanderbilt was William Henry’s seventh child and youngest daughter. She was born in 1860 and married Dr. William Seward Webb, together they had four children. Lila also received a $10 million inheritance from her father, and she used it to build Vermont’s Shelburne Farms.

The farm still runs today and is a model of sustainability. It’s also a nonprofit educational center, and Lila’s husband, son Vanderbilt Webb, and grandson Derick Vanderbilt Webb, all worked on the farm as well.

Late 1800s - 1900s: The Family Took Time to Donate

Even though Commodore wasn’t really bothered with donating to causes and giving his money away, he did make a donation - once. He gave $1,000,000 to what eventually became Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, but that was the first and last moment of giving he had.

But Commodore’s grandchildren were a bit more giving with their money, which wasn’t the best decision for them in the long run. They offered a lot more charitable donations to the people of New York City, from simple things like treating school kids to ice cream to larger donations for young girls’ education and building libraries.

1909: Alva Made Waves With Her Political Equality Association

We know Alva was a prominent woman in society, and she had strong views on the world. She believed very strongly in helping women’s suffrage and was frustrated with how slow things were moving in that area. So she founded the Political Equality Association.

This association helped gain votes for suffrage-supporting New York State politicians and offered education, health, and hygiene resources for the women of America - regardless of their race or class. It also brought education to working women, helping with job training, childcare, and reproductive health.

1926: Mansions Are Torn Down

The stunning mansions that the Vanderbilts built on Fifth Avenue, New York (aka Vanderbilt Row) were sadly taken down in 1926. This was the year that the city started changing and real estate developers began buying land along Fifth Avenue.

The Vanderbilts had spent much of their money, and could not afford to hold onto their houses, and so they were sold and demolished. In their places, skyscrapers were built, paving the way for the modern NYC skyline that we all know and recognize today.

1920s - 1940: Gloria Vanderbilt Overcame a Tough Childhood and Made Her Own Fortune

Daughter of loose-cannon Reginald Vanderbilt, Gloria lost her father early on and her mother was a young widow who became borderline neglectful. Gloria’s aunt, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, took her in and allowed her to have an easier childhood.

After spending her childhood mostly with her aunt, Gloria went to Hollywood as a teenager and then moved back to NYC, going on to study art and acting. In the 70s, Gloria began her jean designs, branching out to other fashion later on. She ended up making a great name for herself and created her very own wealth.

1931: Whitney Museum of American Art Is Another Vanderbilt Legacy

While the Vanderbilt men were (mostly) great businessmen, and often take the spotlight in stories of the family, it’s clear that the women all played major parts in the family’s success as well. One of the ladies, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was a renowned sculptor, art patron, and collector.

She was the second daughter of Cornelius II and married Harry Whitney, giving birth to three children. But she also studied at the Art Students League of New York as well as in Paris. She went on to found the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1931.

Late 1900s: Vanderbilt Money Is Dissolved

While Commodore made and held onto his money, as most wise businessmen do, his descendants were not as financially savvy. This was probably due to them wanting to join high society so badly and could have come from the fact that they didn’t have to work as hard as Commodore did for the money.

Vanderbilt’s children and grandchildren were plagued with expensive tastes, gambling problems, and excessive spending habits. Rather than working harder to secure their position in the shipping and railroad industry, the Vanderbilts soon lost their business footing and their millionaire status. By 1973, much of the wealth had dissolved.

2019: Anderson Cooper Inheritance

Anderson Cooper is a CNN news anchor and the grandson of playboy Reginald Vanderbilt. Since his grandfather squandered most of his inheritance and preferred not to work, Cooper was not expecting to inherit anything, and went on record saying he didn’t “believe in inheriting money."

But Gloria, Anderson’s mother, made her own money. And in 2019, after her death, Cooper inherited his mother’s estate which he had helped her with through the years. The worth of his inheritance was only around $2 million.

If the Vanderbilt's piqued your interest, keep reading to discover the most out-of-this-world rags-to-riches story from the early 20th century. Find out how Sarah Breedlove became Madam C.J. Walker, aka the first female self-made millionaire in America as recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records...

Up next: The Life of Madam C.J. Walker: The First Self-Made Female Millionaire in America

If the Vanderbilt's piqued your interest, keep reading to discover the most out-of-this-world rags-to-riches story from the early 20th century. Find out how Sarah Breedlove became Madam C.J. Walker, aka the first female self-made millionaire in America as recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records...

Up next: The Life of Madam C.J. Walker: The First Self-Made Female Millionaire in America

The Inspirational Life of Madam C. J. Walker: The First Self-Made Female Millionaire in America

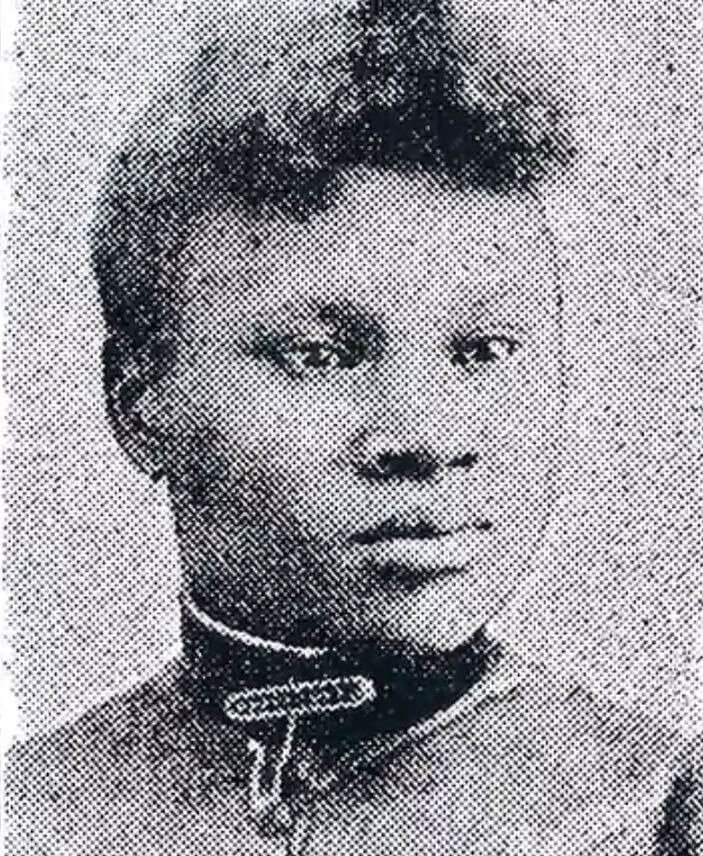

Those who have yet to watch the series Self Made on Netflix, might not be familiar with Madam C.J. Walker. Her story includes a meteoric rise from rags to riches in the early 20th century. So just how did Sarah Breedlove rise to become Madam C.J. Walker, aka the first female self-made millionaire in America as recorded in the Guinness Book of World Records?

Perhaps her story is best told in her own words: “I am a woman who came from the cotton fields of the South. From there I was promoted to the washtub. From there I was promoted to the cook kitchen. And from there I promoted myself into the business of manufacturing hair goods and preparations… I have built my own factory on my own ground.” Of course, this is just a short summary of the business genius that she was. Her story, and the countless it inspired, deserves a detailed retelling.

From Rags: An Overview

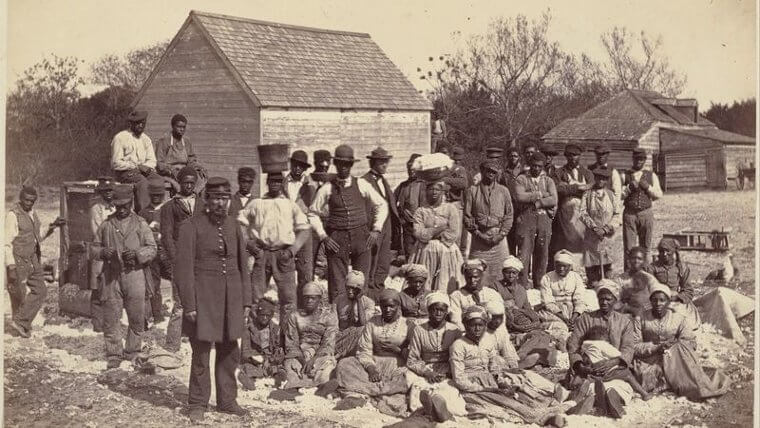

Sarah Breedlove’s story is one of overcoming extreme adversity. To fully understand the importance of her journey to becoming Madam C.J. Walker, it’s vital to start at the beginning. Sarah was born on a plantation in Louisiana and grew up in abject poverty in the 1870s.

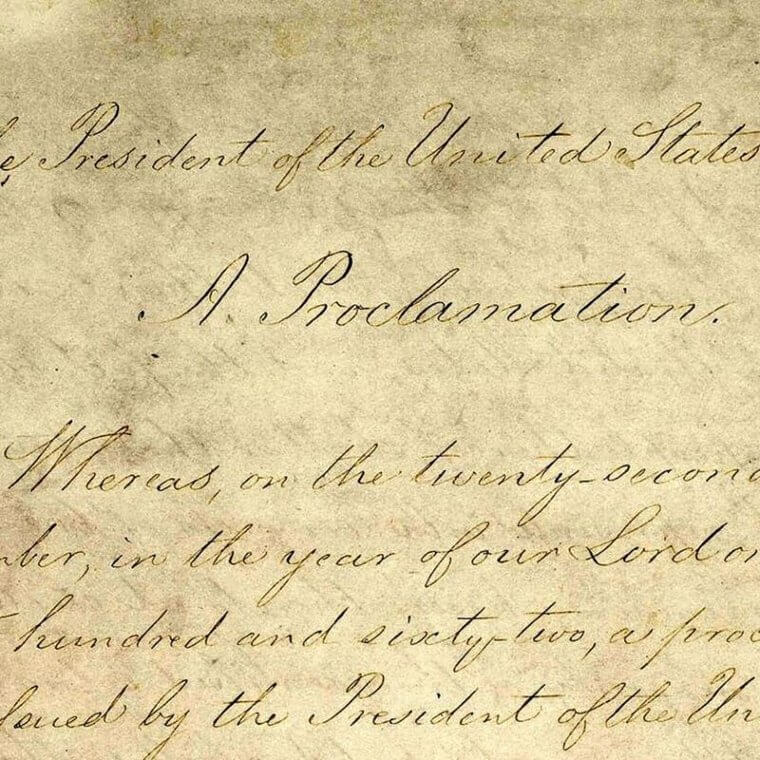

Although she was the first “free” child to be born to her parents, Breedlove still faced extreme adversity. Existing racial divisions didn’t simply disappear after the Emancipation Proclamation. Breedlove would be on the receiving end of much racial and economical prejudice throughout her life.

To Riches: An Overview

With the deck stacked against her, Sarah Breedlove rose from almost nothing to live a life of affluence that many could only dream of. At the time of her passing in 1919 (aged 51), she was known as Madam C.J. Walker and had amassed a fortune exceeding $1m. She also lived in a mansion not far from John D Rockefeller.

Madam C.J. Walker is an icon, and her story is an important part of history. Through her revolutionary hair products, she established her fortune and legacy while also empowering thousands of African-American women to become financially independent.

Born After The Emancipation Proclamation

Sarah Breedlove was born on December 23, 1867, to parents Owen and Minerva Breedlove. Her mother and father had been enslaved by Robert W. Burney on his Madison Parish plantation where she was born, close to Delta, Louisiana.

Sarah was the youngest of her five siblings and the first to be born after President Abraham Lincoln created the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Meaning, not only her parents but her older brothers and sisters had previously been enslaved by Burney. Sarah was the first to be born free.

Free But Still Facing Adversity

Unfortunately, 'free' is a term that is used loosely. Despite being born after the Emancipation Proclamation, the socio-economic and cultural climate during the 1870s was stacked against African-Americans. There was also a shameful level of racially-fuelled violence against this community.

This prejudice is something that Sarah would face repeatedly throughout her life. As a result, her early years were far from easy. After her mother died in 1874 and her father passed the following year, at just seven years old, Sarah was an orphan.

Little-To-No Opportunity in Childhood

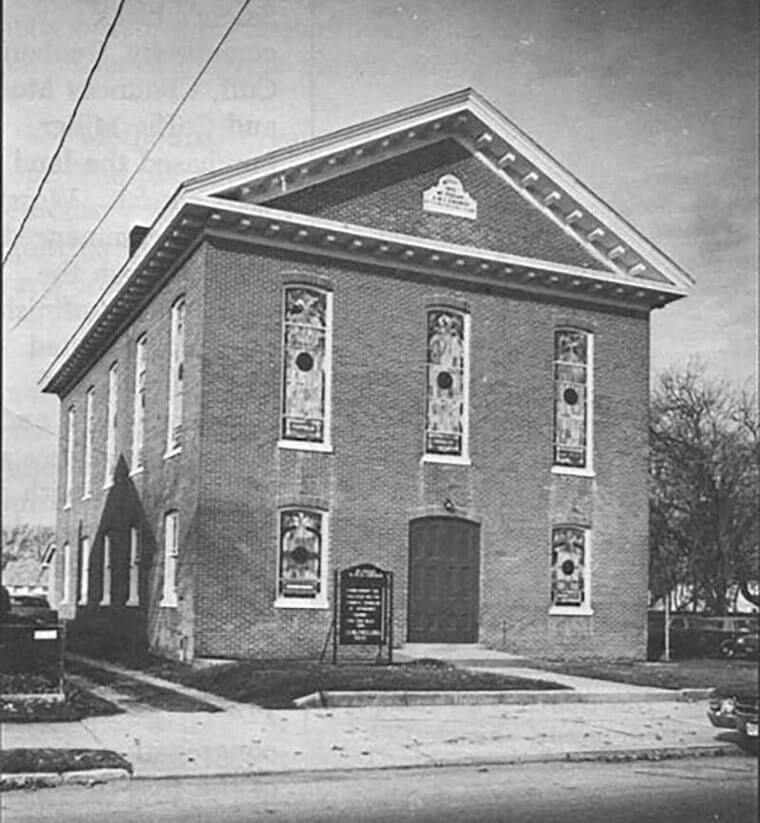

Throughout her childhood, Walker recounts having just three months of formal education. This education took place in her local church during Sunday school literacy lessons.

“I had little or no opportunity when I started out in life, having been left an orphan and being without mother or father since I was seven years of age," she once recalled. After the death of her parents, Sarah lived with her only sister, Louvina, and her abusive brother-in-law, Louvina's husband Jesse.

By Age 10, Sarah Was Working

By 1877, the three relocated to Vicksburg, Warren County, MS. Now age 10, Sarah was already working. There is no documentation to verify her employment, but it is thought that she picked cotton while also serving as domestic help.

Jesse Powell (Sarah’s brother-in-law) is said to have been cruel and abusive. As a result, her home life provided little escape from her working life; a life that was already filled with hard work and prejudice. At this point, Sarah hadn’t come far from the plantation she was born on back in Louisiana.

By Age 14, Sarah Was Married

Sarah had known nothing but poverty since childhood, and now she was experiencing abuse at the hand of her sister’s husband, Jesse. She needed a way out as a matter of survival. By age 14, she was married to a man named Moses Williams.

Marriage became Sarah’s means of escape, and it was for a time. However, Moses sadly passed away five years later, leaving Sarah (now aged 20) to raise their daughter, A'Lelia, alone.

A Widow and a Single Parent

Now a widow and single parent, Sarah and a young A'Lelia, moved to Saint Louis, Missouri in 1888. This was a transformational time in Sarah’s life. Luckily, Sarah’s brothers had already established themselves in Saint Louis.

Her three brothers were barbers, a profession that had slightly more esteem than other roles. It was here that Sarah took up work as a washerwoman. She also wanted to ensure that her daughter received the education that she herself had been denied.

Educating Herself and A’Lelia

Her occupation as a laundress earned her about $1.50 a day. While this was by far from a princely sum, it was enough for Sarah to send A’Lelia to Saint Louis’s public schools - a luxury that she had never experienced herself.

But Sarah wasn’t just passionate about ensuring her daughter’s education, she also worked hard to attain her own. After work, she began attending night school as often as possible. During this time, Sarah married her second husband, John Davis.

Inspired by Her Local Community

As well as working and attending night school, Sarah became active in the local community. Her brothers’ barbershop was located near the St. Paul African Methodist Episcopal Church. The church had developed a reputation for providing African-Americans with a wider outlook on life.

Here, she was inspired by the women of the congregation to seek out a better life for her and A’Lelia. Sarah Breedlove’s great-great-granddaughter, A’Lelia Bundles, has said that these women inspired Sarah to become more than “an illiterate washerwoman.”

Inspired By Her Local Community Continued

Sarah Breedlove was also greatly inspired by the National Association of Coloured Women. The NACW was made up of well-educated black women. They were suffragettes and organized themselves to improve political and social issues.

These inspirational women didn’t just encourage Sarah to educate herself - they were integral catalysts to her later activism and philanthropy. As far as her personal life, Sarah had married John Davis (her second husband) in 1894. They were married for nine years before divorcing in 1903.

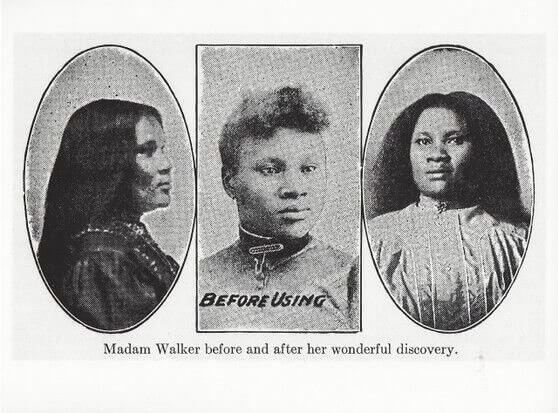

A Personal Struggle With Hair

Like many African-American women of the day, Sarah suffered from a common scalp ailment that caused hair loss. This wasn’t exclusive to Sarah - bad dandruff and scalp infections were a reality for many. This was because the soaps available on the market at the time were extremely harsh.

Poor hygiene and dietary standards also contributed to the prevalence of such scalp disorders. Indoor plumbing wasn’t available to the average American, meaning it wasn’t common to wash hair frequently.

Looking for a Solution

Sarah’s struggle inspired her to look for a fix, especially as she had started to lose her own hair because of her scalp disorder. During the 1890s, she began experimenting with homemade hair remedies combined with the treatments already available in stores.

After seeing positive results on herself, the seeds were planted for her subsequent product line. Although some of the products and ingredients had been around for centuries, Sarah’s aptitude for marketing would set her apart from the crowd.

Working For Annie Turnbo Malone

In 1904, Sarah started working for Annie Turnbo Malone, an influential African-American entrepreneur. Her role involved selling hair care products that were specifically aimed at those within the African American community.

When not at work, Sarah continued to experiment with what would later become her product range. The lessons learned from Malone, as well as her intellectual curiosity, fuelled her to become a pioneering businesswoman. Now age 37, Sarah relocated to Denver, Colorado. She still sold products for Malone, but they would soon be rivals.

Marrying Her Third Husband

The year 1906 was another definitive one for Sarah, both personally and professionally. She married her third husband, Charles Joseph Walker, and started her business. Charles worked in marketing and was crucial in the advertising of Sarah’s hair product range.

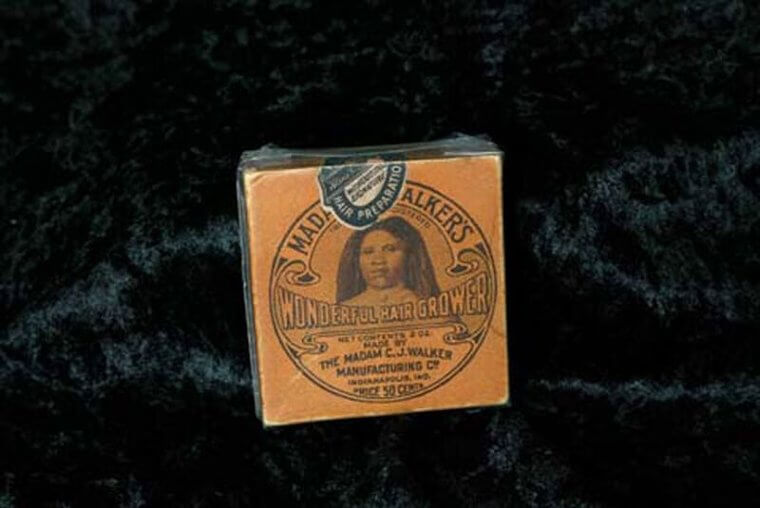

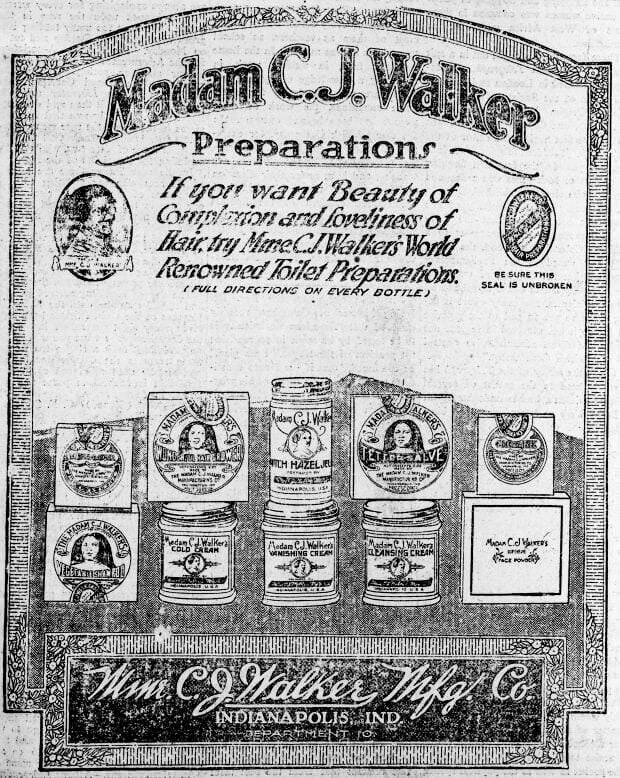

She changed her name to Madam C. J. Walker, with the “Madam” being a reference to female pioneers in the beauty industry in France. Madam Walker began selling her hair treatment, ‘Madam Walker’s Wonderful Hair Grower’ from door to door by herself.

Accusations of Theft

Madam Walker’s hair treatment caused a rift between herself and her previous employer, Annie Malone. Malone accused Walker of stealing her formula, but in reality, the mixture had already been in use for at least a century.

The magic ingredient in the ointment was sulfur, which was an established skin and scalp treatment that had already been recorded in medical texts. The two key differences between Walker and Malone’s approach was that Madam C.J. encouraged washing the hair more frequently, and also had an aptitude for marketing.

Establishing the Family Business

Madam C.J., Charles, and A’Lelia were all involved in the prospering hair care venture. In 1906, A’Lelia was assigned to running their mail-order business in Denver. Now aged 21, she was achieving things her mother might never have imagined when they moved to Saint Louis 18 years prior.

Meanwhile, Madam C.J. and her husband traveled across the southern and eastern United States to further expand the business, during which they experienced racism in many of the places they traveled. Some hotels excluded black people, and Madam C. J. was forced to sit in segregated areas during train journeys.

The Family Business Expands

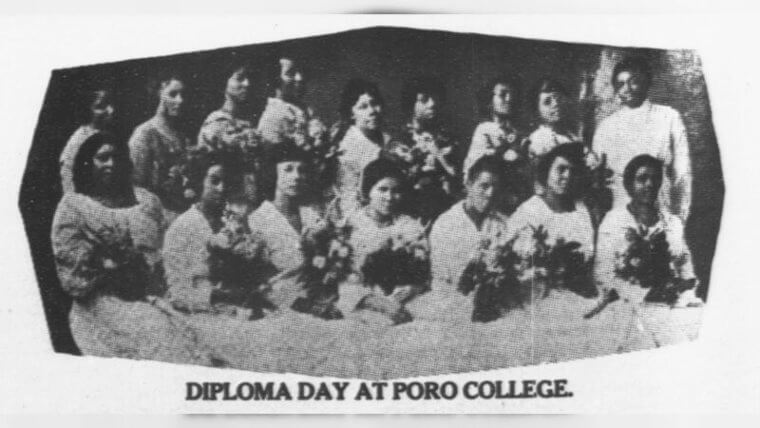

By 1908, the Walker family had moved again, this time to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. While there, they opened up a beauty parlor and created Lelia College to serve as the training ground for future specialists/"hair culturists."

Madam C.J. Walker was on the cusp of achieving not just financial success, but a longstanding legacy among her community. Soon Walker would revolutionize the hair and beauty industry by creating a distribution system for her hair care products while providing training to help empower black communities.

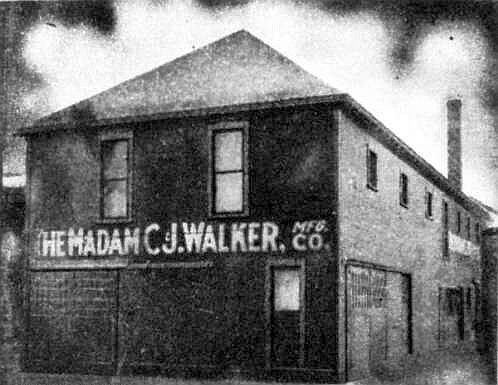

More Branches Of Madam C. J. Walker Are Opened

A'Lelia oversaw the running of their established Pittsburgh branch of Madam C.J. Walker. Meanwhile, Sarah and her husband pushed to open more. First, they opened new branches in Indianapolis, Indiana. There they also established the headquarters for the Madam C. J. Walker Manufacturing Company in 1910.

With her finger on the pulse, A’lelia encouraged her mother to open a beauty salon and office in New York City’s Harlem neighborhood in 1913. Harlem had a large community of African Americans, and their business continued to grow.

Madam C. J. Walker Employed Black Women in Prominent Positions

Madam C.J. Walker is known for being self-made. Because of her earlier struggle, she never shied away from employing hardworking people and helping them to achieve great things. Within her company, Walker employed many black women in prominent positions.

At the time, this was pretty much unheard of and is yet another example of Walker’s pioneering spirit. But she hadn’t finished yet. She had great plans to empower the black community while continuing to expand her business.